I started to feel that I didn’t know roleplaying games well enough so I came up with the plan to read a roleplaying game corebook for every year they have been published. Selection criteria is whatever I find interesting.

In 2004, the game designer Erick Wujcik was one of the guests of honor at Finland’s biggest roleplaying game convention, Ropecon. I told him about how I was making a roleplaying game that didn’t have traditional dice-based mechanics. (This game was published as Joutomaa in my book Roolipelimanifesti in 2005.)

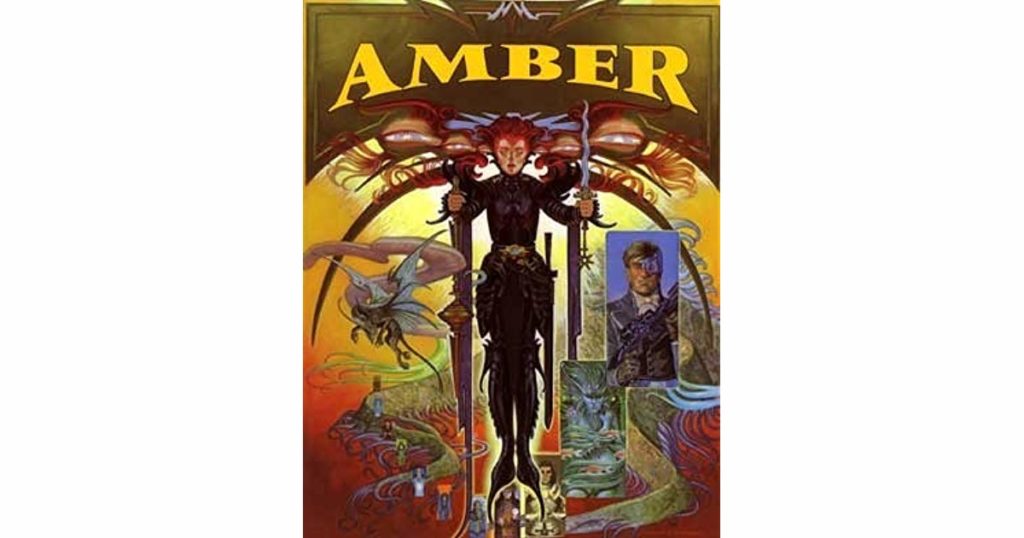

To encourage me, Wujcik gave me a copy of his most famous game, Amber Diceless Role-Playing.

I never managed to read the game, until now. This is embarrassing because Wujcik was totally right: I really would have benefited a great deal from reading it. Going through it now in 2019 was a revelation.

I’ve always felt somewhat alienated from the Anglo-American realm of roleplaying publishing because the style of play doesn’t jibe with how we play in my community. I’ve often jokingly argued that our style was born because we misunderstood the copies of D&D that landed in Helsinki and Turku in the late Eighties. Stupid as we were, we took it seriously when the books waxed poetic about how you should immerse into your character.

The style of play in my community is extremely character focused, involves a lot of freestyle social scenes and encourages player characters to have emotional situations with each other. We have a tendency to be system agnostic because the system is an extra, not the main organizing principle of the game.

Because I’ve done most of my roleplaying in this context, reading published games tends to involve a sense of distance. I can appreciate good design, but the number of books that really spoke to me on a gut level is low.

Against this background, reading Amber was an amazing experience. It felt like the missing link between what I understand roleplaying to be, and most published games, from D&D to storygames.

Amber is based on the novels of the same name by Roger Zelazny. They’re fantasy classics but I’d never read them either. After finding the first pages of the roleplaying game incomprehensible, I read the first Amber novel Nine Princes in Amber and that clarified things a lot.

The setup in both the novels and the game is rather unique. The multiverse is composed of infinite dimensions called Shadows, and the only real constants are the two poles formed by the city of Amber and the Courts of Chaos. The main characters in the novels are the children of the king of Amber, Oberon. In the roleplaying game, the characters are Oberon’s grandchildren, immensely powerful reality-hopping immortals.

Although Amber is indeed diceless, it’s not systemless. Characters are built using points and all things being equal the one with more points in the relevant ability always wins a contest. This means that finding out the capabilities of your enemies is very important, and shifting the contest to an advantageous area is crucial.

Character creation is conducted through an auction where each player bids on various abilities. Thus, only one can be the best in Strength, Psyche, etc.

As a book, Amber is well-written. There’s a wealth of examples and the unusual setting and its affordances are explained clearly. What’s more, the voice of the author and the play community come through in a rare fashion. You get a sense that the book was a product of lots of people playing Amber games.

Wujcik’s way of approaching the source material is also interesting, almost more like literary analysis than world design. He takes care to always make sure you understand what’s from the novels and which parts are his interpretation. To make it clearer, often he presents multiple different options. Thus, you don’t have one stat block for Corwin, but a few so you can choose the one that works best for you.

Because of this approach, the book reads like an attempt to deconstruct the novels and break their concepts into a system of classification using the tools of game design. I suppose all roleplaying game adaptations have to do this, but usually they don’t do it so nakedly as here.

The qualities that I took to so strongly were not really the strange setting or the fun auction system. They were the values concerning what roleplaying was. These are not expressed through hard and fast rules but rather freestyle text explaining the foundations of the game.

Here are some of the values Amber is based on: Good roleplaying is the freestyle social play among the players and the Game Master. Character-based play is intense and rewarding. Roleplaying is a skill for both the players and the Game Master. The purpose of a game book is to help to learn this skill, but once the skill is there, the book can be thrown away. Systems are a tool to help access good roleplaying. They have no inherent value.

In terms of content and the types of events that happen in the game Amber is still kinda American. You face challenges, beat enemies, etc. However, something in those core values was much more recognizable to me than what I read in the vast majority of roleplaying game books.