I started to feel that I didn’t know roleplaying games well enough so I came up with the plan to read a roleplaying game corebook for every year they have been published. Selection criteria is whatever I find interesting.

I’m already way past 1984 in this project but once I learned about DragonRaid, I had to go back. There are not too many Christian learning roleplaying games on the market, after all.

And I’m extremely glad that I did! DragonRaid is a very interesting game, especially considering that it came out in 1984. I’ve noticed that many of the reviews online have a strong focus on the system, understood narrowly as stats and dice rolls. This is a shame because that’s the game’s weakest part. All the best things about DragonRaid lie elsewhere.

There are enough of those best things that I’m going to go ahead and declare DragonRaid a forgotten early classic.

DragonRaid is unusual in the sense that its primary purpose is not entertainment but teaching. It’s intended for Christians who want to learn to be better Christians by playing a learning-oriented roleplaying game. I’m not well versed in the various styles of American Christianity, but to me this seems to come from a fairly strict evangelical viewpoint.

The core idea of DragonRaid is to use a fairly classical fantasy roleplaying game setup to create situations where Christian learning is possible. This religious basis is one of the factors that makes the game so interesting.

Most roleplaying games I’ve ever seen spring from the same pop cultural substrata, whether we’re talking about D&D or Apocalypse World. While DragonRaid superficially pays homage to that same source, underneath its assumptions are those of evangelical Christianity. Because of this, it feels both familiar and fresh at the same time.

The characters are LightRaiders, TwiceBorn servants of the OverLord of Many Names who go to the Dragon Lands on dangerous missions to help further the OverLord’s agenda of salvation. While there, they encounter monsters who symbolize sin and Dragon Slaves, people who can be saved to follow the OverLord.

Everything in DragonRaid is built as a Christian metaphor. The OverLord is Jesus. The Sacred Scrolls are the Bible. The dragons are demons, the mightiest among them representing Satan.

Indeed, DragonRaid is hard to play if you don’t know your Bible. There are spell-like powers called WordRunes. The game mechanic is quite interesting: You cast a WordRune by citing a passage from the Bible from memory, as a player. If you get it right, the in-game effect takes hold.

I’ve read the Bible at one point but I don’t think I would survive some of the challenges in DragonRaid. In one of the adventures provided, The Moonbridge Raid Part I, the characters meet a scholar who is writing a condensed version of the Sacred Scrolls. You can spot an open page and see what he’s saying. If you’re sharp, you notice the small discrepancy between the text and the actual words in the Bible and will be able to challenge him on the issue.

The adventure helpfully suggests that players can have a Bible at hand so they can quickly find the relevant passages to cite.

Bible study really comes into its own in the game’s setpiece encounters, dragon battles. Dragons are spiritual beings who attack the LightRaiders by assaulting their religious beliefs. The dragon tries to wean the LightRaider away from the OverLord and the players have to resort to the Bible to argue successfully if they wish to prevail.

Some of the example arguments provided felt genuinely challenging to me, based on minute Bible knowledge. For example, the Bible describes David both as a sinner and a perfect servant of the Lord. How to resolve this quandary?

If I think about where the design of DragonRaid is located, so much is in the general framing, advice for the Adventure Master, and in the three ready-made adventures provided in the package. To me, these communicate best what DragonRaid is trying to do.

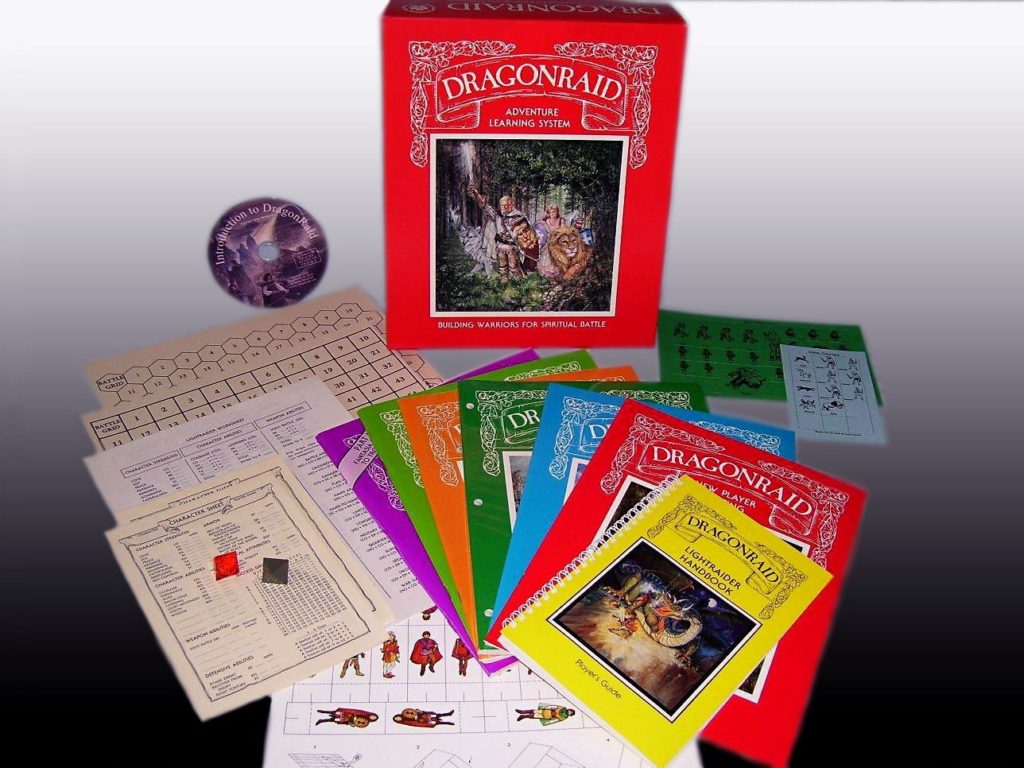

Incidentally, DragonRaid is a sumptuous, extravagant package. It’s hard to think of any other published game box that has this much stuff, except for Invisible Sun. There are seven books, pads of character sheets, a cassette tape that has material helping people to learn the game, battle maps, cardboard figures, dice, etc. There are even multiple copies of a letter explaining the goals of DragonRaid, apparently so players can all read them around the table simultaneously.

The game describes itself as a learning tool, and it does shine in terms of how the material is presented. DragonRaid is a very user-friendly package. There’s a ton of handouts, some included in multiple copies so that you don’t have to make copies yourself. The game’s systems and concepts are presented in a very pedagogical manner, cleanly and readably. One of the seven books included is an extra rules reference in case multiple people want to check the rules at the same time. The three adventures follow a clear progression: The LightRaider Test introduces basic concepts, The Rescue of the Sacred Scrolls has a castle the characters explore and The Moonbridge Raid Part I is a hexcrawl.

Indeed, in terms of presentation and making its substance understood, DragonRaid has few equals in the roleplaying field even today.

Still, there are some barriers to play. The game suggests that the Adventure Master should be someone with spiritual authority. Although you can play with non-Christians, the game is not designed for that. For these reasons, it would be impossible for me to run the game exactly as written.

The system is clearly a product of it’s time. It’s quite light, and made more interesting by the fact that stats are various virtues, such as Love and Gentleness. It’s strongly combat-focused, despite the fact that the game has a conflicted, uncertain relationship with combat.

The adventure design is fairly rudimentary. Perhaps we can call that too “a product of its time”. The adventures are interesting but even the hexcrawl manages to have some very linear components.

Still, the interesting parts shine. One of my favorites was the game’s attitude towards those staple activities of Dungeons & Dragons, killing and stealing. You see, killing is wrong. A LightRaider doesn’t go around killing people. Killing monsters is acceptable, but only because they are metaphors for various sins, as the game expressly notes.

Stealing is also wrong, even from your enemies. It’s a sin, including if you’re literally confronted with a dragon’s hoard.

Sometimes the game is downright charming. Characters can assume different classes. My favorite is the BearKnight, a LightRaider who rides a talking bear. You can even use a lance!

There are also plenty of talking animals who are all personal emissaries of the OverLord. So when a muskrat starts talking to you, better listen!

One of the most original elements in the adventures are the scenes in heaven. Once your character dies, you get one final scene where they enter the beyond. These scenes are quite atmospheric, and some even contain the possibility of learning new information about the game world. To me, this felt more like modern Fastaval-style design than anything you’d find in an Eighties American roleplaying game.

There are some silly things about DragonRaid. The humor doesn’t always land, or perhaps the cultural gulf between contemporary Finland and the evangelical America of 1984 is simply too wide. Still, I decided not to talk about those things in this text because I feel DragonRaid deserves to be re-examined as a pioneering early roleplaying game decidedly ahead of its time.

In one adventure, the characters encounter rotting fish. The Adventure Master is told to get an actual spoiled fish and set it on the gaming table to provide authentic atmosphere. You don’t find that advice in Eighties D&D.