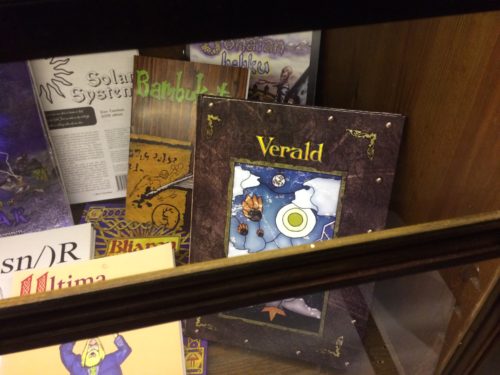

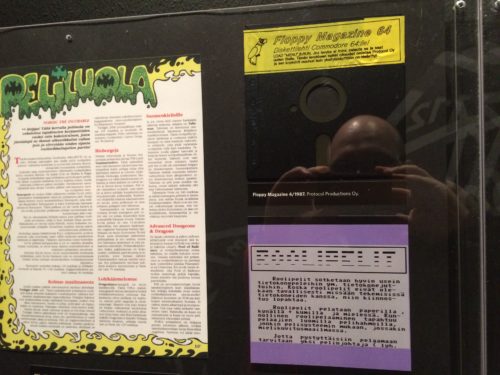

The Finnish Museum of Games opened a new exhibit on the history of tabletop roleplaying games in Finland yesterday. It’s wonderful stuff and I expected the feelings of nostalgia revisiting all these old things brought me. But the real surprise was in how much there was I’d never heard of before. The exhibit takes an extremely comprehensive, diligent approach to its subject, and because of this even a veteran roleplayer who lived through the era will find something new.

From a personal perspective, it felt strange to see parts of my own history move behind the glass of a museum exhibit. Sometimes literally, as I was startled to find a character brief I’d written for another player years ago on display. It was from the tabletop campaign Tähti by Mike Pohjola, later published as a book.

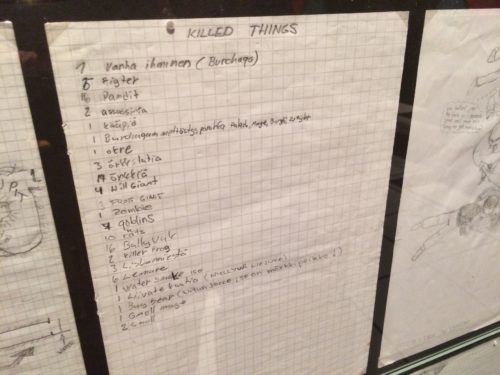

Other times, the maps drawn by hand on graph paper were not from my campaigns, but they could well have been. They’re from people who started playing as kids, often American fantasy roleplaying games translated into Finnish. It’s funny to imagine what those kids would have said if told that in a few decades, their squiggles would be museum-worthy.

Many of these relics are from people who would become game designers themselves, including James Edward Raggi IV of Lamentations of the Flame Princess fame who’s old home campaign maps are now on display.

From a wider perspective, the exhibit is part of an interesting process where as we grow older, we become more conscious of our own history. We want to preserve it and make it understood. It’s wonderful that the exhibit is not only about the history of games as publications, but makes a serious effort to include the actual experiences of people playing roleplaying games.

This is especially important in Finland because the emergent play culture didn’t always reflect the cultures that produced the games we started with. A young kid in Helsinki or Kouvola automatically played D&D with different assumptions than the American designers who made it.