I’ve been running a game based on Vampire: the Masquerade these past few years, and when I started it, I realized I had to adapt it quite a lot to make it work for me.

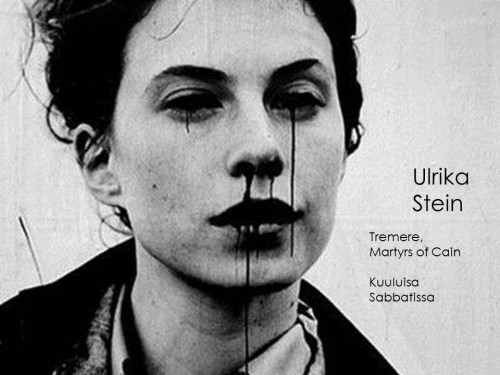

I’ve run three versions of my campaign Verikartta, and characters from each game have visited the others. All are set in London, but approach the vampire society from different angles. In Verikartta A, the characters were made into vampires by important high-society vampires. In B, they were illegal vampires created in random and chaotic circumstances by criminals and losers. C, still running, is the Sabbat game, and distinctly different from the other two.

Lately, I’ve been doing something I probably should have done a decade ago, which is to read Vampire: the Requiem. It’s been interesting to see how they modified the game and compare it to what I have done.

Some changes are identical: In Requiem, they’ve injected the world with mystery, so instead of ancient vampires with superior knowledge of the world, we have ancient but delusional monsters who can’t separate their fantasies from real memories. Masquerade’s overarching explanations have been replaced by local mythologies.

One of the more crippling features of Masquerade is the static nature of its vampire societies, especially if you play a young vampire. In Requiem, age is not necessarily power and it’s possible for young vampires to do important things. Masquerade’s Eternal Vampire World Government has been replaced by various local situations.

Reading the book also makes it obvious to me that the Requiem and the Masquerade are very specific vampire roleplaying games, with their own themes and approaches. In Requiem, the idea of “a game of personal horror” has been brought to the fore even more strongly than in the Masquerade, and the anti-social, miserable horror of being a vampire is heightened. The inner conflicts core to the game are rigidly controlled by game mechanics, even more so than in the previous game.

My version grew sort of organically, partly designed and partly improvised, but reading this book makes me think I diverged more than I realized, especially on the core themes.

In my version, it’s not really a “storytelling game of personal horror” at all. There’s horror to be sure, and I’m struggling to describe how it works. Maybe the “game of communal horror”? In the sense that the horrors of the world mostly make themselves manifest in the way the supernatural communities work, and how that affects individuals. All vampires play games, and the characters have to play too unless they want to be overrun. Issues of social class govern interactions both inside vampire society, and between vampires and other supernatural creatures.

When I started the game, I decided to chuck the personality rules such as Nature, Demeanor, Humanity, Virtues, the Beast, etc. out the window. Being a vampire is essentially really cool in a simple, physical sense. Requiem makes being a vampire seem like a real struggle, and I ran games like that when I originally played Vampire in the Nineties. This time, I wanted to see what would happen if being a vampire was essentially a wonderful, privileged state, especially if you let go of your morals. Almost everyone around you already has.