This is a series of posts where I play 100 boardgames.

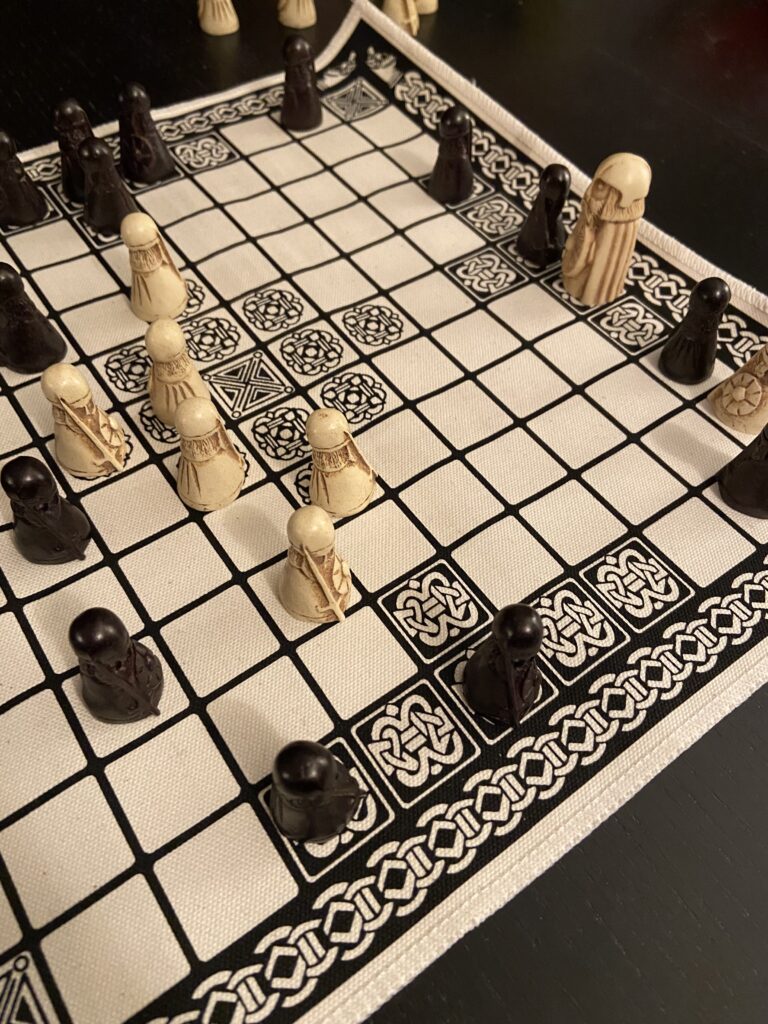

Game: Hnefatafl

Designer: Unknown

Year: 400 CE

Country: Nordics

Publisher: History Craft Ltd

Hnefatafl, also known as the Viking Game and King’s Table, is a Northern European boardgame played roughly between the 5th and 18th centuries. Or so I’m reading on Wikipedia, but in fact it was also played in my living room just a few hours ago!

Similar to chess, Hnefatafl is a strategy game with no random element where you can plan your moves and anticipate your opponent. The interesting thing is that is asymmetrical, with different goals and positions for the two players. One plays a king under siege, the other the sieging army. The king’s goal is to escape, while the goal of the siege is to capture the king.

You can imagine it as a game version of the classic genre trope where the heroes stop the villain’s plan, but the villain tries to escape at the last moment.

There are only two kinds of pieces, soldiers and the king. All move like the rook in chess, and to capture a soldier you need to move one of your pieces on both sides of an enemy piece. To win, the sieging side needs to have a soldier on all four sides of the king. The king escapes if he reaches one of the four corners of the board.

At times, gameplay resembles a high-attrition game of chess where one player is running away with the king and the other tries for a checkmate using their few remaining pieces.

In play, the game had significant strategic depth. One of the most consistently interesting moves was to go between two enemy pieces yourself. If an enemy got you surrounded like this, you lost the piece, but if you made the move yourself, you didn’t. What happens in practice is that your enemy takes a piece, and then you move another into that same place.

Every time this happened in our play, it felt audacious, even transgressive. Often, it was also tactically useful.

Chess is often described as an abstraction of warfare, but let’s face it: You got to imagine pretty damn hard to see it. Chess is so abstract and it doesn’t feel like there’s a story behind whatever combat it purportedly simulates.

In contrast, the asymmetrical setup of Hnefatafl lent itself to much richer narrativization. It seems important that the king is escaping, and leaving his soldiers behind. It’s possible to visualize a gang of raiders laying siege to a viking fort, trying to capture a wily ruler who’s sneaking away. This lent drama to the action of the soldiers on the board even when they’re just identical gamepieces.

We played four games of Hnefatafl and during that time, the game revealed significant variety. It often rewarded patient play where you tried to goad the opponent into making an aggressive move so you could trap them. The king in Hnefatafl is not the decrepit wreck found in chess but a bold, fast-moving viking warrior running around the field with enemies at his heels!