I wrote this article for the now defunct roleplaying magazine Playground. It went under before this got published, so here it is. If you want to read old issues of Playground, they’re all here.

Better Dead Than Red

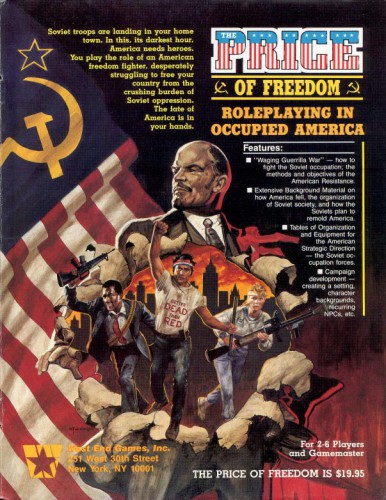

Playing the right-wing roleplaying game The Price of Freedom.

The Communist party elite is scrambling away in panic. There has been a huge explosion on the stage, shredding the traitor Jack Reed’s body into pieces. The players have a short discussion whether firing a rocket launcher into the crowd is justified.

It goes something like this:

“I didn’t get to fire my rocket launcher.”

“All Communist sympathizers are traitors.”

“All right then.”

I’m running a game of Greg Costikyan’s anti-Soviet roleplaying game The Price of Freedom, published in 1986. It’s an early example of a political roleplaying game, well ahead of its time both because of its design innovations and its contemporary setting. We’re playing the game because we want to explore political games other than the left-wing orthodoxy of Nordic games such as Kapo and Mellan himmel och hav.

A note to liberal readers

A probably unique feature in all of roleplaying publishing, The Price of Freedom’s Player Book contains a “Note to Liberal Readers”. Among other things, it says that: “The Price of Freedom is a fantasy roleplaying game in the true sense of the word; its fantasy is the right-wing nightmare that America is delivered into the hands of her enemies.” It instructs the players to think of the game as “The Lord of the Rings meets William F. Buckley“.

Indeed, the game seems specifically intended for a player of a certain political persuasion: it contains many conservative slogans such as “Don’t tread on me” and “Free minds, free markets”. I asked the designer Greg Costikyan about it, and he explained that the idea was to capitalize on the conservative fanbase of Twilight 2000, a post-apocalyptic military game popular at that time. “I wanted to out-do Twilight 2000, in a way”, Costikyan says.

“My political views are not those of The Price of Freedom; at the time, I considered myself a ‘left libertarian'”, he continues. “I supported free markets and the minimal state, but had a suspicion of large businesses and their frequent attempts to use the power of the state to exclude or diminish competition, and largely supported unions as a counterpoint to the power of big business. And, of course, strongly supported civil liberties.”

This makes The Price of Freedom something of an oddity, a conservative game designed by a non-conservative designer wishing to sell games to conservatives.

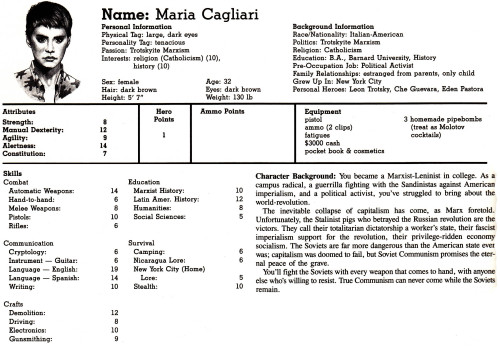

Sometimes, reading the materials provided with the game, you get the feeling the designer is attempting to make something sensible out of a bizarre premise. The premade characters provided with the game run the gamut of anti-Soviet resistance: one is a rock star defending rock’n’roll, another is a vigilante cop who believes that the scum should be cleaned off the streets. Perhaps the strangest character is Maria Cagliari, a committed Trotskyite who fought against the Contras in Nicaragua and believes that Stalin betrayed the Revolution. The player who played Maria in our game said that it was particularly difficult to be a left-wing character in a right-wing game. In our game, Maria immediately found common ground with the vigilante cop: both believed in extreme solutions.

(A sample character from The Price of Freedom.)

Death to traitors

I used to believe that it would be impossible to use roleplaying games for the purposes of political propaganda. Players had too much agency, too many opportunities to subvert the message.

I no longer believe this.

We set out to play The Price of Freedom as seriously as possible. According to the game book, things were supposed to be grim and heroic. The introductory adventure included with the game hadn’t aged especially well, but I used as many story beats from it and other adventure ideas in the game as I could.

Many of these were about how to sell the mindset of the game to the players. The game says that tragedy is a great way to motivate characters. Having the Soviet enemy perpetrate atrocities against your family and friends gives you the proper mindset to kill. With this in mind, in the beginning of my game a turncoat in the players’ resistance cell killed Moshe, an elderly veteran of the Polish guerrilla fight against the Nazis. As he died, Moshe gave a speech on the importance of freedom, resistance and killing snitches.

We discovered that once you decided to try to get into the game’s atmosphere, it was quite easy. Moshe’s speech was crude and obvious, but also fulfilled its intended purpose. When the characters finally caught up with the snitch, an old man and a friend of Moshe’s from the days of the Polish resistance, they executed him in cold blood.

Indeed, the game says that players should enjoy the license to kill without having to feel bad about it. According to the Player Book: “Let’s face it, we’d all like to blow things up. We’d all like to crush our enemies. Fortunately, society forbids us to act on those impulses. The Price of Freedom releases those emotions. And as a result, it can be a gas.”

And it was. Of all the design ideas, this concept of freeing the players from the moral qualms of extreme violence worked the best. One player said it was liberating to just kill people without all the moral agonizing that goes on in the games she usually plays. Costikyan describes the game as a “power fantasy, albeit with a darker setting than most”.

The propaganda beats of The Price of Freedom work, if you let them. For a player who’s intent on subverting the game, it doesn’t do a thing. But for a player who’s open to the message, I believe it can work quite well. Of course, the Soviet threat is no longer quite as germane as it once was, but I’m sure that other, more contemporary propaganda games work this way too.

Gutless President

The folder with the sample characters contains a summary of the events that led to the Soviet invasion of the US. It begins with: “A gutless President has been elected.” The Price of Freedom makes its politics obvious with slogans and conservative fears. The game doesn’t say whether the “gutless President” is Jimmy Carter or Ronald Reagan, but we can hazard a guess.

The game wasn’t particularly well received. “Some of my more liberal friends were intrigued by the idea, but repulsed by the heavy-handed nature of its political message”, Costikyan says. “But in general, you know, it was a flop. We had quite a lot of interest from the distributors pre-publication, but in the event, it did not sell particularly well. Keep in mind that this was the Gorbachev era, US-Soviet relations were improving, and the scenario was viewed as pretty implausible.”

Perhaps unhappy with it himself, Costikyan concludes by saying that he’s: “A tad embarrassed by the game”. Despite his misgivings and the Red Dawn -style premise and politics, I think The Price of Freedom has aged surprisingly well. It’s a great antidote for the idea that roleplaying is inherently utopian. Sometimes the message is: “Eat hot lead, Commie dog!”

(A slogan from The Price of Freedom.)

Extra

Can’t play this

A book doesn’t change even if the original audience is long gone. Its interpretations may change, but the text itself remains the same.

Playing a roleplaying game is a different matter. Since running the game depends on our own creative contribution, we simply cannot experience the game as it was intended to be experienced in 1986.

Every roleplaying game is designed with an audience in mind. The Price of Freedom is clearly and explicitly meant to be played by conservative U.S. players living in 1986. The recommended mode of play is the “avatar campaign”, a game in which players play themselves in the event of Soviet invasion of the U.S.

Playing such a game is impossible for us. We’re not politically conservative, and the Soviet Union can’t invade us because it doesn’t exist. We don’t live in the U.S. and it’s not the Eighties. One of us was even born in the Soviet Union, further complicating the us-vs-them setup of the game.

We decided to play The Price of Freedom with the ready-made characters provided with the game, and use the intended setting of 1986 America. This already makes the game different from what it was designed to be. Without its audience, The Price of Freedom ceases to be.